How to Read Rhythm

So far, you have learned how to read the notes on the staff and how to find those notes on the fretboard.

Now, let’s look at how long to play each note for.

Rhythm notation is the symbols used to tell us how long to play each note.

Rhythm notation is so important that even modern Guitar TAB uses it.

The shape of the dots on the staff represent different lengths of notes.

Note Symbols

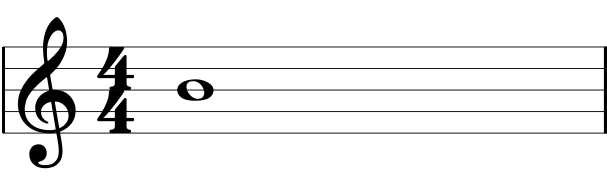

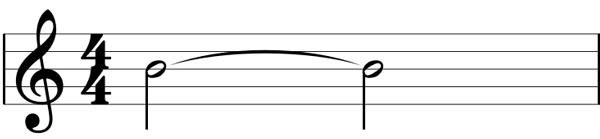

The first note symbol is a widened circle:

This note is called a whole note (American terminology) or semibreve (British terminology) and lasts for four beats.

Note: there are two names for every type of note – an American name and a British name. It doesn’t matter where you live, I recommend learning both names so you can understand all musicians.

If there are four beats in a bar (known as 4/4 time), a whole note will last the entire bar.

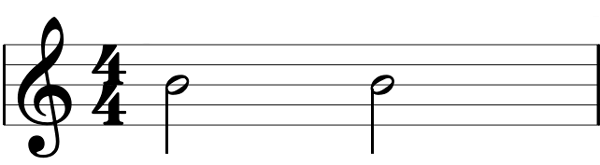

If you see a note that looks like a whole note but has a stem (vertical line) attached to it, this is called a half note (American) or minim (British).

A half note lasts for two beats. The stem can either point up or down to make the sheet music look easier to read (eg: high notes will have the stem point down and low notes will have the stem point up).

If a half note’s circle is filled in black, this is a quarter note (American) or crotchet (British) and lasts for one beat.

Most of the time when you count 1 – 2 – 3 – 4 in your head to the beat of the music, you are counting in quarter notes.

If you see a black note with a stem and a tail, this is

an eighth note (American) or quaver (British) and lasts for half a beat.

As you can see above, an eighth note can either have a tail at the top of the stem, or it can be connected to another eighth note with a beam (it can be connected to all of the below notes as well).

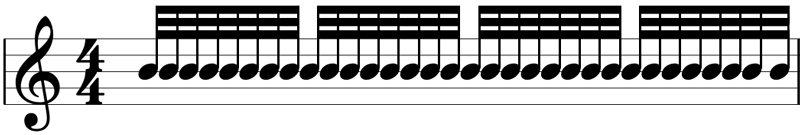

A black note with two tails or two connecting beams is a sixteenth note (American) or semiquaver (British) and lasts for a quarter of a beat.

You can see that each type of note is half the length of the previous note symbol.

We can continue adding tails or beams to the notes to continue to halve the note length.

So if you see a note with three tails or beams, it is

a thirty-second note or demisemiquaver and lasts for an eighth of a beat.

This can continue to sixty-fourth notes and further, but you are unlikely to see anything past thirty-second notes.

Rest Symbols

All of the above symbols are used to tell you how long

to play a note. But what about when you don’t want to play a note?

Rest symbols are used to tell you how long to play nothing but silence.

For each of the above note symbols, there is a matching rest symbol.

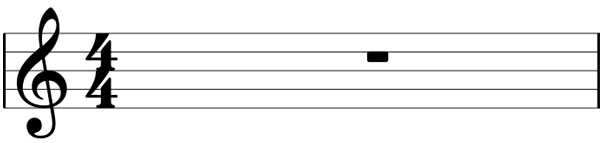

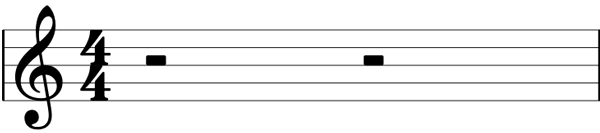

Here is a whole rest symbol which lasts for four beats (same as a whole note):

Here is a half rest symbol which lasts for two beats:

When comparing the whole and half rest symbols, look at how the blocks connect to the lines. A whole rest symbol touches the second line and the half rest symbol sits on the third line.

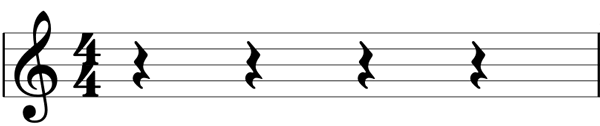

Here is a quarter rest symbol which lasts for one beat:

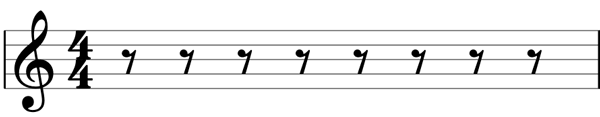

Here is an eighth rest symbol which lasts for half a beat:

Here is a sixteenth rest symbol which lasts for a quarter of a beat:

As you can see, a sixteenth rest symbol doubles up the eighth rest symbol which is similar to how a sixteenth note uses two beams instead of one.

You can probably guess what a thirty-second rest looks like if you follow the above example:

This same pattern continues, but you’re unlikely to see shorter rests than this.

Any combination of the above symbols can be used in a bar as long as the total length of rests and notes adds up to the correct number of beats (explained later).

Dotted Notes

You might notice that each new symbol halves the

length of the previous one. But what if we want to play a three-beat note or a one-and-a-half beat note?

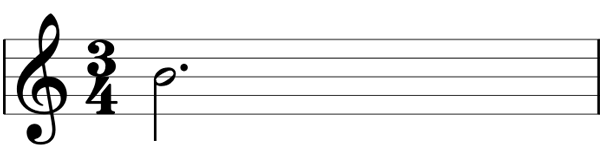

There’s a simple way to do this and it is called a dotted note:

By placing a dot to the side of a note or rest symbol, it means that symbol lasts for one-and-a-half what it would normally last for.

To figure out the length of the dotted note, you multiply the original note length by 1.5.

So if the symbol is a one beat note, a dot next to it means to play it for one-and-a-half beats (1 x 1.5 = 1.5).

If a dot is next to a half note (two beats), it now lasts for three beats (2 x 1.5 = 3). You can see a three-beat note in the above example.

Any note or rest symbol can have a dot next to it to change the duration.

Tuplets

What happens if you have a four-beat bar but you want to play three notes evenly throughout the bar?

A Tuplet is when you divide the beat into irregular values that don’t line up with normal note lengths. Tuplets can quickly become complicated, so I’ll keep the examples basic.

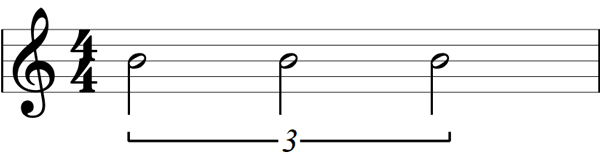

The below example shows how you can play three notes spread over four beats:

Normally, each of the above notes lasts for two beats. That means there would be six beats in the bar – which doesn’t work when there are only four beats in a bar.

The bracket and ‘3’ under the notes tells us to play these as tuplets.

When there is a ‘3’ in the bracket, this is called

a triplet. A triplet is one of many different types of tuplets and the most common you will see.

An easy way of thinking about this is that the 3 tells us to play these three notes in the time of two notes. Two of these notes adds up to four beats, so that’s why this bar works.

Here is another example of triplets using eighth notes:

Normally, three of these notes would add up to one- and-a-half beats. If you count up all of the eighth notes, you’ll notice there are too many to fit in the bar.

But when eighth notes are played as triplets, they are played in the time of two eighth notes (one beat).

Tuplets can become really confusing when they are grouped in numbers higher than 3, so for now, just be aware that they can exist.

How to Read Chords

Now that you know how to read notes, rests, and the rest of the staff, you can start learning music!

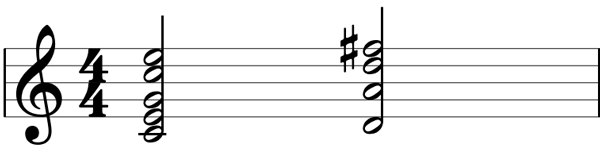

Chords are easy to read in standard notation as you only need to remember one thing: when notes are stacked on top of each other, they are played at the same time.

A chord is simply a bunch of notes stacked on top of each other as shown below:

It will take some time for you to get used to reading chords and it will be slow at first as you will need to figure out each individual note.

Over time, you will learn to identify chords instantly without having to stop and figure out each individual note.

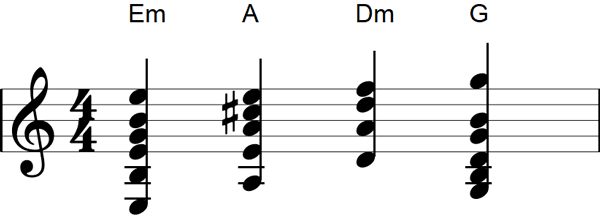

Here are some common chords in standard notation:

A limitation of standard notation is that it doesn’t tell you where to play these notes (it’s rare to see notation to say which string to play the notes on). So you need to figure out whether these chords should be played open or as barre chords.

How to Read Time

Signatures

It’s important to know how many beats are in a bar. Some songs follow the typical 4-beat pattern (eg: 1 2 3 4 1 2 3 4), others use a 3-beat pattern (eg: 1 2 3 1 2 3), while others are a bit more complicated.

You can tell how many beats are in a bar by reading the time signatures at the start of the staff as well as any time the beats change.

Time signatures are also known as meter

signatures or measure signatures.

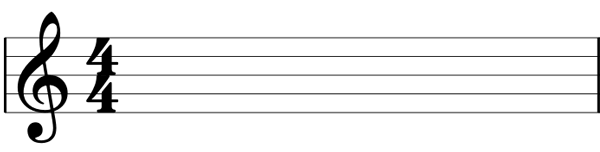

In the above example, you can see that the song starts in 4/4 time (say: four four time).

What this means is that there are four beats in a bar (the top number) and each beat lasts for a quarter (the bottom number).

Have a look at the below example and what the time signature means:

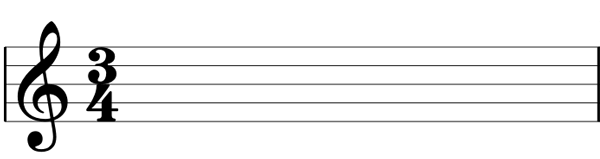

This time signature is telling us that there are three beats in a bar (top number) and each beat lasts for a quarter (bottom number). We call this 3/4 time (say: three four time).

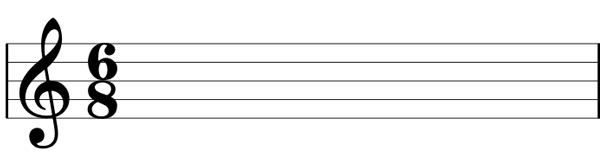

The bottom number isn’t always 4, but it is the most common you will see. Here is an example of 6/8 time:

This time signature means there are six beats in a bar and each beat lasts for an eighth.

3/4 vs 6/8 time |

If you compare 3/4 time and 6/8 time, you might notice that as fractions they are exactly the same. The difference between 3/4 time and 6/8 time is how it feels and how you count. In 3/4 time, we count ‘1 2 3 1 2 3’. In 6/8 time, we count ‘1 2 3 4 5 6 1 2 3 4 5 6’. If the tempo is the same for both examples, we would be counting the beats in 6/8 time twice as fast as we count the beats in 3/4. They may look the same, but the way we think about and feel the music changes. |

Music genres like jazz and fusion often incorporate complex time signatures, leading to frequent changes in the number of beats per bar.

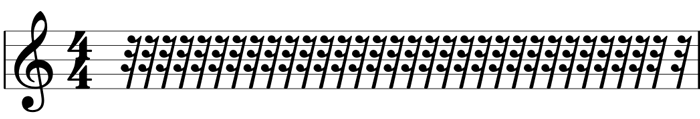

Here is an extreme example from Dream Theater’s The Dance of Eternity:

You can see that almost every bar changes time signatures. The example starts in 4/4 time before changing to 7/8 time.

A 7/8 time signature means there are seven beats per bar and each beat lasts for an eighth. Think of it as seven eighth notes in a row.

Remember that this is an extreme example, so you’re unlikely to see time signatures like 13/16 or 17/16.

Odd time signatures (with an odd number on top) aren’t very common.

A lot of songs stick to only one time signature, so you’re likely to only see a time signature at the very start of the sheet music.

But keep an eye out for any changes so you can continue to properly count the beat.

How to Read Key Signatures

If a song is written using the C Major scale (C D E F G A B), you’re unlikely to see any sharp or flat notes.

But what if we’re playing with a scale that uses a lot of sharp or flat notes?

Having a lot of sharp or flat notes can quickly make sheet music hard to read. Take a look at the below example and how cluttered the sharp symbols make it to read:

This can be tricky to read because even the notes without sharp symbols may be sharp if a sharp symbol was previously used in the bar. There are two notes above that don’t have sharp symbols but are still sharp notes!

Fortunately, there is a different way of writing sheet music that makes it easier to read.

A key signature basically takes all of the sharp or flat symbols you would use throughout the bar and places it at the start.

Here is the above example again, but this time it uses a key signature:

Notice all of the sharps after the Treble clef? That’s a key signature.

What this means is that each time you see a sharp symbol in the key signature, it’s telling you to play that note as a sharp from now on.

So the first sharp symbol we see is on the top line, the note F. This key signature is telling us that every time we see an F (in any octave), we need to play F# instead.

There are five sharp symbols in this key signature, so there are five notes that we need to remember to play sharp instead of natural.

Here is a simpler example:

This key signature has one flat note on the middle line, which represents the note B. This key signature is telling us to play B-flat instead of B from now on.

All of the other notes stay the same, but when we get to what looks like B, we need to remember to play B flat.

Key signatures aren’t always used. Sometimes the person writing the sheet music will use sharps and flats throughout the piece, while other people will use key signatures.

A key signature can change at any time, so lookout for new signatures.

There is a key signature for every major scale. So the above key signature with one flat is the key signature for the scale F Major. The earlier key signature with five sharps is the key signature for B Major.

The circle of fifths is a really useful resource to understand key signatures and major scales. I’m currently writing a guide on the circle of fifths,

so subscribe to updates here to be notified when it is available.

How to Read Tempo

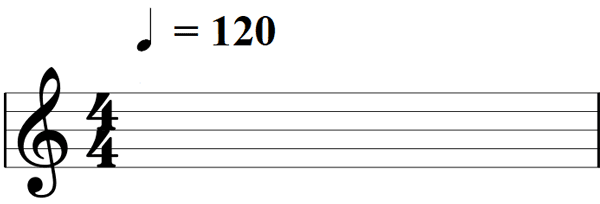

The song’s tempo is usually indicated at the start of any sheet music as shown below:

The tempo of a song is indicated by this number, showing the beats per minute. For example, a tempo of 60 means 60 beats per minute (one beat every second), while a tempo of 120 bpm means two beats per second.

If you want to find out how fast any tempo is, all you need is a simple metronome.

If you're looking for a more modern solution, you could use an online metronome tool. However, there are also smartphone apps that offer metronome features for convenience.

The tempo of a song can change, so keep an eye out for tempo symbols throughout the sheet music.

How to Read Music Symbols

Just like how sheet music uses different symbols to represent musical notes and rhythms, standard notation also utilizes symbols to convey musical information.

If you already know how to read the symbols used in Guitar TAB, you will find many of the symbols used in standard notation easier to read.

Here are the most common symbols you are likely to see and what they mean.

Curved Lines

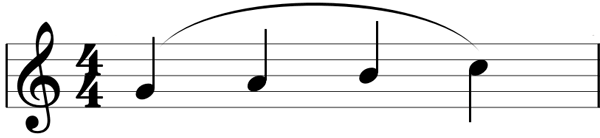

A curved line can mean two different things. If a curved

line connects two notes together of the same pitch, it is called a tie:

A tie is telling us that the second note is a continuation of the first note. In other words, you keep holding that first note and don’t pick it again.

Ties can connect notes together in the same bar and they can also carried over to the next bar as shown below:

In the above example, the last note in the bar continues to ring out for two beats in the second bar.

To work out the total length of a note, you add up the lengths of all of the notes under the tie (more than two notes can be tied together).

If a curved line connects different notes together (two or more), this is the symbol for legato.

Legato is when you pick the first note, but don’t pick the next notes. Hammer-ons, pull-offs, slides, and tapping are all forms of legato.

Sometimes sheet music will use H or S along with a curved line to tell you to play hammer-ons or pull-offs as shown below:

In the above example, you pick the note G, then hammer-on to A. Then you pick the note B and hammer-on to C.

If you see a sloped line connecting the notes as well as a curved line as shown below, that’s telling you to play a slide.

The letters sl. may also appear to indicate slides.

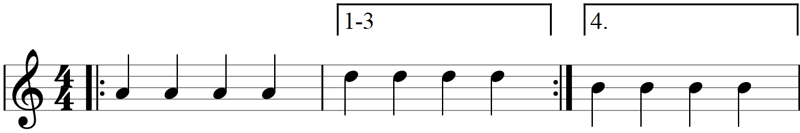

Repeat Signs

When a part of a song is repeated over and over (eg: a riff that keeps repeating throughout the song), instead of writing the bar over and over, a repeat sign can be used.

There are two parts of a repeat sign: the start and the end as shown below:

The double vertical lines and the two dots are used at the start and end of the section that is to be repeated.

The above example is telling us to play the four notes, then play the four notes again before moving on to the next bar.

A single bar can be repeated or a long section can be repeated. The dots are always on the inside of the bar lines of the section to be repeated.

If a bar is to be repeated more than twice, it will tell you with a number above the end repeat sign as shown below:

This example is telling us to repeat the bar three times before continuing.

Alternate Endings

Quite often, something will repeat a few times, then on the last repetition, there will be a slight change.

Instead of having to write the entire section out, we can use alternate endingsto repeat everything except the last bar.

What the above example means is that the first three times, you repeat the first two bars. Then on the fourth time, you play the first bar, then you skip ahead and play the third bar.

The numbers tell you what to play on each repetition. That’s why we play the third bar (labeled with 4) on the fourth repetition and skip the second bar (labeled with 1-3).

Alternate endings may seem confusing at first, but they make sheet music much easier to read as you can seriously cut down on how many pages it takes to write out a song.

Shuffle Feel

Some music doesn’t have what is known as a ‘straight

feel’. In music such as blues, it might have a ‘shuffle feel’.

Instead of re-writing sheet music to match the rhythm of something with a shuffle feel, we can write the music as normal and add a shuffle feel symbol as shown below:

What this means is that instead of playing eighth notes as normal (eg: 1 and 2 and 3 and 4 and), you play them with a shuffle feel (eg: 1 and2 and3 and4).

While the above notes look evenly spaced, they’re played with a shuffle.

There are different types of shuffles you could use, but the above example with eighth notes is the most common.

Finger Numbers

While it is uncommon, you might be lucky and sheet

music may include some suggestions on what fingers to use.

In the above example, the number next to the first note is a recommendation on which finger to use.

Index finger is 1, middle finger is 2, ring finger is 3, and pinky is 4.

Sometimes most of the notes will be given numbers, but it’s more common to see the first number of a part with a number. Then you need to figure out the other fingers on your own.

Normally once you know which finger to start with, it’s pretty easy to figure out the rest.

String Numbers

A limitation of standard notation is that the notes on

the staff don’t tell you where to play them on the fretboard.

For example, an E in the top space on the staff could be played on six different positions (if you have a 24 fret guitar).

It’s rare, but you might be lucky and sheet music will tell you which string a note is to be played on using a number in a circle.

In the above example, the first note is to be played on the fifth string.

Typically, this notation is only found on a couple of notes, leaving you to determine the remainder.

Standard notation also includes various other symbols that are important to understand when reading music, but the examples provided above should be a good starting point for beginners.

It can be advantageous to learn both standard notation and Guitar TAB since most sheet music incorporates a mix of the two.

How To Read Rhythm